On the waterfront

Voices / Landscapes (for the eye and ear)

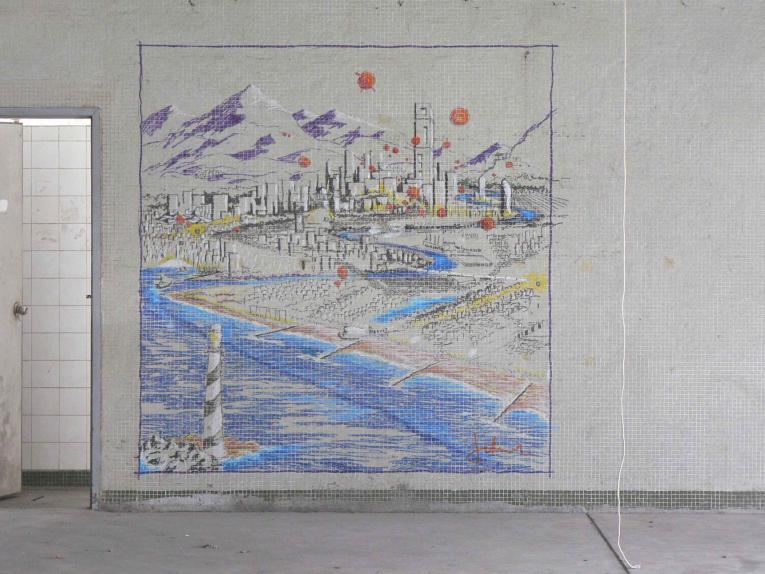

Starting from 26th September, on the occasion of the 2014 edition of Around, the works of four artists – Michael Graeve, Tetsuya Umeda, Paolo Piscitelli and Phill Niblock – will be adding their voices to the familiar sounds and noises present at the Kwun Tong Pier in Hong Kong: sounds which are both natural, such as the lapping of the waves, the birds singing, the voices of the passengers preparing to board the ferryboat, and ‘artificial’, like the engines of the boats docking or departing, the noise of the foghorn, and the muffled sounds of the cars driving on the overpass above the pier.

As a part of their installations – made out of carefully selected objects which are subsequently pieced together – Michael Graeve and Tutseya Umeda will be creating ephemeral events that the audience will witness as they are taking place, by keeping their eyes wide open and pricking up their ears.

For his performances, Michael Graeve usually mounts a substantial and apparently chaotic collection of old sound-transmission systems, such as record players, amplifiers, speakers, jumbled with a number of monochromatic panels he painted himself. He then slowly and patiently proceeds to make sounds with those objects just by manually working on them, without resorting to any disk, tape, or other storage device. There are no previous recordings, nothing is repeated twice: each system issues sounds on the spot for the first time - and sometimes also for the last, when they irreparably break down under Graeve’s mechanical stress during his performance on the installation. Graeve moves around like a ‘sound hunter’, searching for precarious harmonies and rhythms, which both he and the audience will be listening to for the first time.

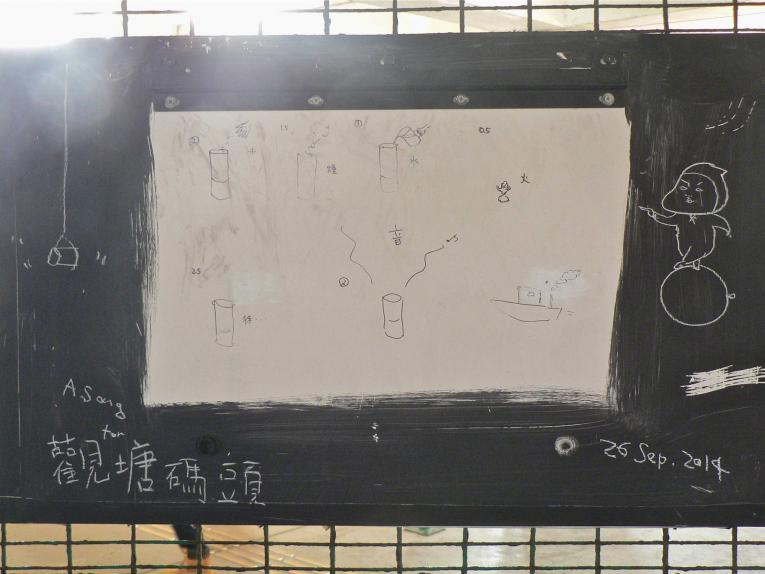

Tetsuya Umeda assembles a number of assorted objects, which he always collects close to the locations where he will perform. In these installations there is a bit of everything, that is, anything which – interacting with other selected elements – is able to trigger phenomena that will produce sound, noise, heat, cold, and sometimes emissions of smoke and light. During the happening, Umeda is completely absorbed by seemingly senseless activities, which he carries out with extreme care and concentration. As a matter of fact, both his performances and his installations seem to carry no particular meaning, that is, he places no conceptual significance on them. Nevertheless, what happens is indeed extremely meaningful, since it pertains to specific physical phenomena, there is no fiction, no representation. The heat emanating from the flame of a gas stove, the cold given off by a piece of synthetic ice, the force of the weights which carry objects up and down by means of rope winches: these are all absolutely genuine phenomena, and Umeda’s task consists in managing them, that is, activating them, so that they can take place. He thus creates situations, which, once set in motion, are often hard for him to significantly control or influence. Not unlike Graeve, Umeda is always absorbed in his performances, he knows he should stay focused, avoiding any distraction: however, this doesn’t convey anxiety to the viewer, because both artists have a certain levity about them, their respective performances are marked by fluidity, and all events take place in a natural manner.

In an interview with Tetsuya Umeda, I found a sentence that perfectly describes an approach to reality which emerges distinctly from his work: “from the viewpoint of a zero year-old”. However, this is the same approach I also noticed in Michael Graeve's movements, when he cautiously wanders around his chaotic installations – all his senses fully alert – attracted and guided by the reverberation of sounds and colours, seeking fleeting melodies, which he will stop to listen for a few seconds, along with us, ecstatic and fascinated as we are.

Also at the pier, close to the installations of these two artists, the discreet but persistent presence of At the same time, by Paolo Piscitelli, with its wall clock, will mark the real time on location, while the sounds issuing from the speaker (recorded in 2008 with a camera microphone, in the surroundings of his own studio) will establish a virtual connection to another time and space. And Phill Niblock’s Topolò 1 installation will depict a video loop of a simple yet fascinating phenomenon: a resounding roar of water falling on the liquid surface of a fountain, forming air bubbles. The action is repeated in slow motion, with the sound also slowed down: this produces a somewhat trance-like, alienating effect on the viewer.

In another area of the city, at the Connecting Space in Fortress Hill, videos by Carlos Casas, Paolo Piscitelli, Phill Niblock and Alessandro Quaranta will be screened. They have all been shot with a similar approach: the artists see/listen to the landscape in an all-encompassing manner, leaving out nothing of what happens in front of the camera. Namely, they record casual events, often straddling the border between what is visible and what isn’t, just as they are taking place, like butterflies suddenly appearing and being followed briefly as they fly.

Carlos Casas’ videos are very slow, accurate explorations of a certain location. He uses both static shots, subsequently edited, as in the case of Pool, and slow tracking shots, starting from a small built-up area, and ending on the woods close by, as in Smoke; he also uses an extremely slow 360° tracking shot, which follows the same route for three times in a row, as in Dead Sea. Each time, Casas uses two sound recording processes, one which records ambience, and the other which captures shortwave radio signals, at exactly the same time as the shot takes place. In the case of Smoke, one can hear the noises coming from a canteen in the work camp in Patagonia where Carlos shot the video; the voices of the Argentine singer Sandro, and of a host – both issuing from an Argentine radio station – have the same relevance on the frequency spectrum as the sounds from the canteen. As far as Pool is concerned, the radio waves (also rigorously recorded live at the same time and in the same location) stand out much more than the ambience sound does: as time goes by, and day turns into night, one can hear them more and more clearly, as the images of the abandoned swimming pool grow dimmer and more insubstantial, till they fade into darkness. In Dead Sea, as the sun is setting, the muezzin’s voice - recorded from a shortwave radio station – stands out, distorted and floating through the air, but in stark contrast with the desert and the absolute silence of the landscape. One can just hear a weird background disturbance, like an electric accompaniment.

The video showcased by Alessandro Quaranta, The Changing of the Guard, relies chiefly on the counterpoint between the ambience sound – especially the voices of the young protagonists – and the silent sections, purposely created by the author; towards the end of the video, the sound is once again fully audible, and this has a strong impact on the viewer, who feels like he’s fluctuating between a dream-like dimension and a more worldly one. This can be compared to what we experience when, whilst dreaming, we are abruptly woken up by a noise, and we aren't sure if it came from the dream itself or from the external world. Phill Niblock’s Topolò 2 piece is a fifteen-minute-long video featuring real images, which – due to their shape and colour – have something psychedelic about them. Shot in 2006 during the festival in the small Italian village of the same name, it’s an experience of sheer contemplation for the eye and ear. While the loud and crisp sound of the water dripping from a roaring mountain spring (which is, however, never filmed by the camera) ceaselessly underscores the slowly moving images, we see a roundish form (it’s a plum, unidentifiable, since it’s been zoomed in on quite a lot and its wet surface is reflecting some trees overhead), which seems to float, surrounded by and partly submerged in water. Both plum and water continuously change colour, from green to blue and vice versa, faintly mirroring objects (especially the crowns of the trees) close by.

Paolo Piscitelli, in his labor #3, sets about lightly sweeping the surface of a table covered in a layer of clay, repeating a very specific gesture with his left arm, using it as if it was a windscreen wiper on a car. He thus determines a series of slight changes on the surface itself, which swiftly takes on the appearance of a windswept glade or sandy coastline. Even though the camera carries on recording what happens on that small surface, the viewer is under the impression that he's standing before a vast landscape. The sounds – recorded by the author in the immediate vicinity of the studio where the performance takes place – emphasize the feeling of alienation: they reveal actions that seem incongruous with Piscitelli’s, but which soon acquire a semblance of plausibility, as if they actually stemmed from the performer’s activity.

Carlo Fossati, 2014 (translated by Valentina Maffucci)

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Elaine Ho on Around 2014.pdf | 56.28 KB |